Cultural Significance & Heritage:

Explore the rich cultural heritage and significance of Pounamu in Māori tradition, and discover its deep-rooted importance in Aotearoa New Zealand.

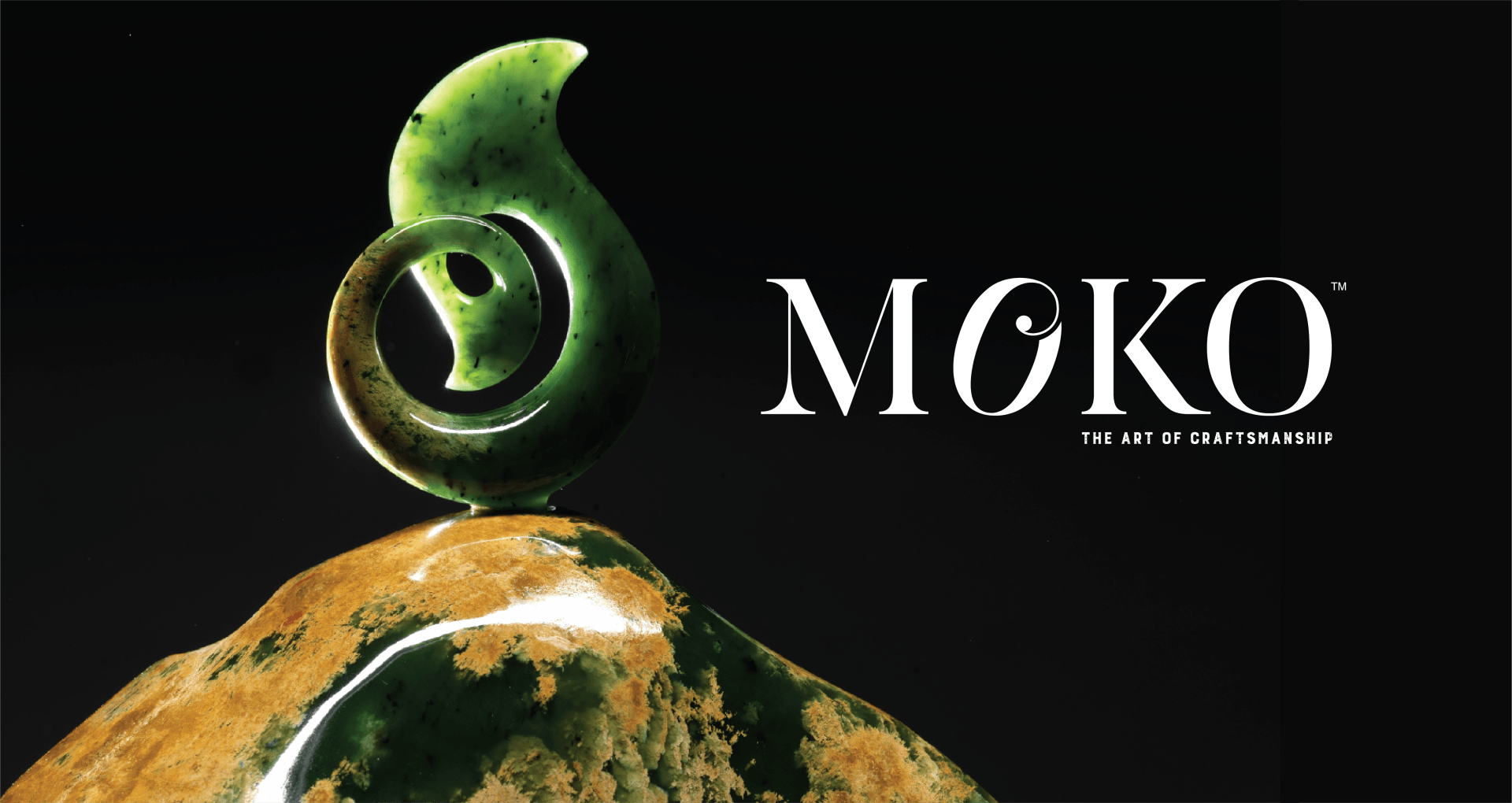

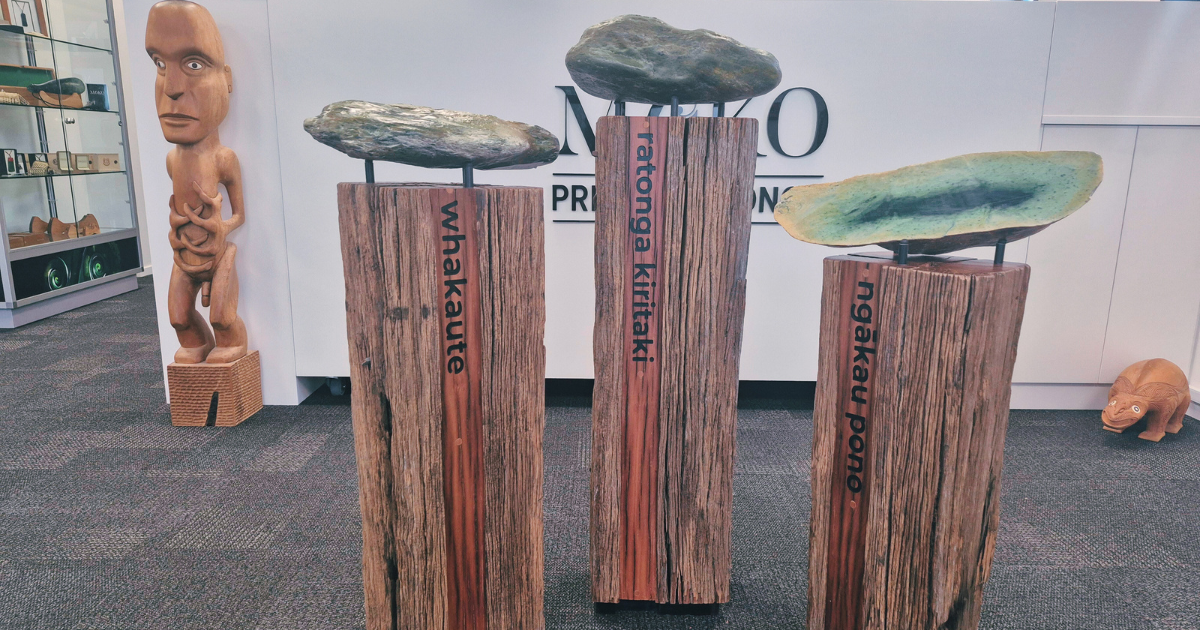

Moko Pounamu Knowledge Library

We believe that gifting pounamu is a profound act, one that deserves to be supported by deep knowledge, genuine care, and absolute integrity. This belief is the foundation of our business, which is built on three core pillars that guide every interaction, both in our Christchurch shop and across the globe.

As the Southern Hemisphere settles into winter and the nights grow longer, many New Zealanders have become familiar with watching for Matariki to signal the beginning of the Māori New Year - and a public holiday to enjoy with our families. But there's another celestial guide that deserves our attention, particularly here in the South Island: Puanga, the brilliant star that serves as an equally significant marker for this sacred time of year.

According to tradition, pounamu was born from Papatūānuku. Her tears of sorrow and joy flowed into the rivers of Te Waipounamu (the South Island) after her separation from Ranginui (the Sky Father). These tears crystalised into pounamu, imbuing the stone with her mauri (life force) and mana (spiritual power).

I can find no other record of the Orient adventure mentioned by Mr W Lyon in the closing remarks of his lecture on the various geological strata of New Zealand to the merchants of an aspirant young Wellington, though both the schooners ‘Royal Mail’ and ‘Anita’ plied these islands in the 1840s. These early days of Colony present both risk and opportunity to bold and entrepreneurial ship owners and masters. I can well imagine the idea of a couple of holds full of ‘New Zealand jade’ landed in Shanghai at £1500 a ton inspiring just such a speculative enterprise. There is a record of the ‘Anita’ arriving in Port Nicholson (Wellington) on Christmas Eve 1842 from Manilla so It’s certainly not beyond the realms of possibility that the crew of Anita made it back to New Zealand just in time for Christmas dinner, cashed up presumably, after a dash up to China with a hold full of Tangiwai, the bowenite lookalike to nephrite jade that Piopiotahi or ‘Milford Haven’ is known for when it comes to pounamu, technically speaking however, bowenite is not jade. F or want of nothing more than a start date I’m going to assume that this was the first reported commercial, industrial scale international export of pounamu from Aotearoa. With that in mind, we can say that it was a business that lasted just over 100 years, 1842 - 1947, though the Milford - China run seems a one-off transaction in the record, albeit conceivably several hundred tons worth. Between 1842 and 1866 however, the record is more or less silent. I think it’s reasonable to assume that there will have been moments of opportunity in the interim, just as there was prior to 1842. Tucker the Sydney souvenir trader for example, the chancer whom we met in chapter five dying his death at Murdering Beach, Otago in 1817.

In the story of Poutini’s Shore, the convergence of gold and greenstone would seem as inevitable as the tide. Wherever there are legends of treasure, human desire will follow and human nature will reveal. In January 1864, Simon the Maori strikes payable gold beneath a pounamu boulder in the Hohonu river, a tributary of the Taramakau that rises in the Hohonu Range above the southern shore of Lake Brunner. Haimona Tuakau - ‘Simon the Maori’ - Haimona Tuangau, all one and the same man of unique and singular character, his reputation as ‘the hardest working and most useful man in Westland’ was already well established by the advent of the West Coast gold rush brought about in no small part by his own discovery on the Hohonu. According to Mr J C Revell of the Canterbury Provincial Government office in Greymouth, it is also noted that ‘Simon brought over from Christchurch via Harpers Pass to Mawhera on February 11th, 1864, the first two horses to come to that district…’ I can find no other reference to this remarkable moment of pioneering enterprise but I’d bet all the amalgam in my only piece of bling, a pennyweight at least, that they were two pack horses purchased with his find, to help him haul out the real treasure, a great slab of pounamu that once nestled in the Hohonu on a little pile of gold. Prospectors had been washing colour on the West Coast of South Island, then called West Canterbury, since the late 1850s, but colour in the pan alone does not make a gold rush. Worth anything from £2 to £4 an ounce in the 1860s, payable gold meant the ‘digger’ still came out ahead after the usual expenses had been deducted i.e. food, transport, accomodation and stores, which more often than not would include a healthy supply of grog, deemed an essential tonic of the soul for many a hardy pioneer adventurer to ‘the poor man’s diggings’. And pioneers they were, the diggers who made there way to Hokitika, Charleston, Waimangaroa, The Mokihinui, The Taramakau, The Berlins and Lyell on the Buller, and other momentary places that played out fast or never got going or promised just enough to drive a man drunk and ruin him. The prospector Albert Hunt is one of the diggers credited with sparking the rush to the coast, apparently with a 20 oz find in the Hohonu, also called the Greenstone river, sometime between April and July 1864, so naming the goldfield there as the Hohonu Greenstone field. It is almost certain that Haimona Tuangau was the man who pointed Hunt in that particular direction. Hunt knew Tuangau from his time spent waylaid and frustrated at Mawhera Pa around May 1864, urgent in his quest to strike it rich and claim the £1000 prize offered by the Canterbury Provincial Council for finding payable gold in West Canterbury. Tuangau lived at Mawhera but also had a whare in the Taramakau, near the Hohonu, where he and his friend Samuel Iwikau te Aika often prospected. It is known that Hunt travelled down to the Hohonu with the two Maori prospectors around this time. History seems a little uncertain about Albert Hunt, by turns generous or scathing as hero or hoaxer, with William Smart, another prospector who found his way to the Hohonu Greenstone at the same time, accusing Hunt of outright deception in his attempt to claim the Provincial Council prize. But diggers would soon descend on the Hohonu Greenstone field once Hunt and Smart put the word out. By February of 1865 the West Coast rush was on with news in the Christchurch Press that some 2375 ounces of gold had lately been shipped from ‘Okitika’. By the end of 1866 over half a million ounces of gold had been extracted from the alluvial fields of the west, and the town of Hokitika was booming. Around December 1865 another prospector, James Reynolds, was on the Hohonu river seeking his fortune in both gold and greenstone, which you’d have to say is a sound business model given terrain of such fortunate geology, when he came across a large slab of pounamu in the bush quite near the stream at a place now called Maori Point if you look at a map of the area. The pounamu had clearly been placed there, and appeared to have been worked at over time, though perhaps not recently. Reynolds then regarded the pounamu slab as an abandoned ‘claim’ and staked it out as the Goldfields Act allowed of any abandoned ‘claim’ on a government declared goldfield. Remembering Haimona Tuangau’s original find of ‘payable gold beneath a pounamu boulder’, we now return for a moment to January 1864 and the circumstances of ’Simon the Maori’s’ discovery. William Martin, a friend of Haimona Tuangau, himself a prospector in the Hohonu in 1863, lately a carpenter and bailiff in Christchurch, gives this account, having offered Tuangau a finders fee of £50 if he could locate any payable gold: ‘January 1864, his mate, Samuel (a Maori) [Iwikau] and himself [Tuakau] went up the Hohuna River, and on its main branch (the Greenstone Creek) they found an embedded boulder of pure greenstone, which, with the aid of levers cut in the bush, they eventually rolled out of it’s deep bed in the stream, and by rolling with the fall of the creek, placed the boulder in the bush out of sight and floods. An hour or two afterwards they went to the spot where the boulder had lain, with the discoloured water away, and on the side and bottom, embedded in the debris, they clearly saw shining in the clear water lumps of gold from one pennyweight to four or five, and, to use Simon’s own words, he said: ‘We take out our sheath knives and we take all we see, and I say to Samuel we want big hammer to break up the greenstone, and I say we no tell we find gold, but we go make a walk to Christchurch. We find Martina, get £50, buy big spawl hammer, bring Martina back with us, when we then tell all the Maoris, and all the Maoris go with us, get plenty of gold, we go to Christchurch and speak to many mans, but no one knows you. We make a walk about all day and see many men making the house, but we no see you working. We get very tired, buy a hammer, and go back to Kaiapoi, then we come home’. Haimona Tuangau’s interest in gold, it seems to me, was pragmatic. His interest in pounamu came from a different deeper place. William Martin’s account shows us something, it shows us that Tuangau had exercised a claim of ownership over the greenstone boulder, evident by his actions, and therein exists a property right. Importantly, that right is one of custom, of tradition. It is a Maori right and it is permanent. The great greenstone trial of 1866 will decide if the Maori right has any standing in law because the greenstone slab found and claimed by Reynolds was the same pounamu boulder put there by Haimona Tuangau when he found his gold. Subsequent to staking out the pounamu boulder another Pākeha on the Hohonu, Bill Chappell, informed Reynolds that he had no claim on it, that in fact he (Chappell) was ‘looking after the boulder for the Maoris’. Mr Revell, the Warden at Greymouth would later support this view; ‘The stone you have taken possession of belongs to Simon Tuangau and I think you had better not touch it’. Revell was of the opinion that because Tuangau found the boulder before the Goldfields Act applied in the Hohonu Greenstone field, the issue was one of property, not a mining claim. Reynolds approached Tuangau directly, looking for a deal. Tuangau declined. Reynolds brought explosives to the site and broke up the boulder yielding nearly 1900 pounds of pounamu worth an estimated £2500, roughly equivalent to around 1000 ounces of gold. Tuangau slapped a writ on Reynolds, and police seized the pounamu on the authority of a warrant issued by the resident magistrate at Greymouth. Reynolds brought his own action against Tuangau alleging unlawful detention of the greenstone and commencing criminal proceedings. The case went to the Supreme Court in Hokitika and then in August 1866, after two juries failed to reach agreement, was referred by the presiding Judge on a point of law to the Court of Appeal in Wellington. In the event, the Court of Appeal ruled in favour of Tuangau, accepting the argument that a traditional property right predated goldfield regulations. Haimona Tuangau was able to show he had asserted that right. Werita Tainui, a Ngāti Waewae Rangatira testified, in Maori, that ‘Simon’ had asked him to break pieces from the stone soon after it was found and that under native law, the stone belonged to Tuangau, even if left unattended for long periods. Revell as well, also gave evidence in support of Tuangau. In October 1866 the Court of Appeal, in a unanimous decision, found that a property right based on custom and tradition lay with Haimona ‘Simon’ Tuangau, a Maori, and awarded him costs. Epilogue:

On the question of whether or not to bless the greenstone - ka whakatapu te pounamu - you must first ask yourself the bigger question, ‘What do I believe?’ Hold that thought for a while, and let’s consider context. Today in Aotearoa New Zealand I think most of us would agree that pounamu, or greenstone if you like, is, for want of a better term, our national stone. We regard it as taonga, a treasure. We can imagine that it somehow belongs to all of us, is part of us, reflective of our sense of ourselves and of the land from which it emerges. The very human facility of incorporating story into our realm of understanding allows us to enhance this view with certain intangible qualities that add dimension to the idea. We can add spiritual aspects to physical things. We can imply unseen forces to visible phenomena. We can put god into the machine. And, it has to be said, we can take god out again if it suits. With regard to pounamu we can observe these transitions from the physical to the metaphysical and back again. It’s a god stone and a commodity. Another question seems to arise in realtion to this particular topic of discussion and that is, can I acquire greenstone for myself? Can I buy a piece of pounamu just for me? It’s a widely held ‘belief’ in Aotearoa that you should only acquire greenstone in order to make it a gift. If we covet it for ourselves, bad luck will surely follow. It’s a lovely sentiment with a slightly sinister flip side. Of course, if it were true, it would put the commerce of pounamu in something of an awkward position. And let’s not be shy about it, pounamu has commercial value. It’s a semiprecious stone, it’s nephrite, it’s jade, it’s beautiful, enigmatic, mysterious. In the hands of an Artisan its value multiplies. What are we to make of this apparent conundrum? I think we can accept that our modern day views, opinions and beliefs regarding pounamu emanates from Te Ao Māori - the Māori World - and the tikanga thereof, which are the practices and traditions that attend the stone itself. We’ve already seen in previous discussions the pre- eminent position of pounamu in Māori life. In Maori material culture, you’d have to say that pounamu was very much the gold standard. It’s important to keep this in mind when we consider that the culture encountered by Captain Cook and to a lesser extent, Abel Tasman, was mercantile, though Tasman didn’t hang around long enough to discover that. But Māori have always liked a good trade, a deal where both sides think they got the better. Trade means transaction and engagement with others. Trade means communication of ideas and practices. Trade is outward looking. It seeks alliance and arrangement in lieu of conflict. And of course, trade seeks goods. Pounamu as a commodity was not alien to Māori. Pounamu as a source of material wealth was a given. So Pounamu with all its qualities both physical AND spiritual, was immensely valuable. Ngāi Tahu understood this, conquering West Coast hapu to secure the resource and establishing trade routes and workshops to generate and guarantee supply. Te Rauparaha of Ngāti Toa understood this as well when he sought to wrest control of Te Waipounamu South Island from Ngāi Tahu and secure the resource for his own. Such is the mana of the stone that wars are fought for it. When Pākeha took a shine to the stone, another layer of value was added as pounamu went international and the world would come to know greenstone from New Zealand. But economic value is only ever part of the equation, unless you’re a neoliberal. Thankfully I’m not here to argue economic theory. I’m here to discuss the other gods in the room.

This mere pounamu resides within the guardianship of the Canterbury Museum. It finds itself in good company there with whānau gifted from all parts of the motu. We do not yet know it by name but we can be sure a name exists. This is an intimate weapon. This is warfare up close and personal - kanohi ki te kanohi - face to face in the fight. It is the weapon of a rangatira, of a chief. Great mana attends it. But this weapon came to the attention of its present caretakers long after the battles were over. This particular mere pounamu represents an engagement of a different kind. According to Wikipedia ‘The Montgomery baronetcy, of Stanhope in the County of Peebles, was created in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom on 16 July 1766 for the Scottish lawyer and politician James Montgomery. The second Baronet represented Peeblesshire in Parliament. The third Baronet represented both Peebles and Selkirk in Parliament.. . . The seventh Baronet was Lord-Lieutenant of Kinross-shire. He assumed the surname Purvis-Russell-Montgomery in 1906.’ The eighth Baronet, Sir Basil, though he bore the full monicker, preferred the more modest ‘Montgomery’. He took up the title in 1947 after the death of his father. He lived at 77 Totara Street, Fendalton, Christchurch, South Island, New Zealand. Julia Bradshaw of the Canterbury Museum informs us that in October 1949 Sir Basil gifted the mere along with a beautiful kahukiwi (Kiwi feather cloak), a pounamu kohei (a long slender pendant of greenstone), a small pounamu heitiki and a sharks tooth. The Baronet’s gifts are inextricably bound to his whakapapa. They tie him to this land, and willingly so in my opinion.

‘… a piece of green talk [sic] about two & half inches long, and an inch & half broad, flat, and carved into the figure of a most uncooth animal of fancy'. William Brougham Monkhouse (Munkhouse), ships surgeon on HMB (His Majesty’s Bark) Endeavour (1769-1770), describing a hei tiki worn by a Māori encountered in New Zealand. It was Monkhouse who shot Te Rakau at Turanganui (Gisborne) where Cook first made landfall in Aotearoa. Monkhouse would never see England again. He died in Jakarta of dysentery on the journey home. ‘As they have no metal, their adzes and axes are made of a black stone, or of a green talc which is not only hard but tough ... Their axes they value above all that they possess, and never would part with one of them for anything that we could give. I once offered one of the best axes I had in the ship, besides a number of other things, for one of them, but the owner would not sell it; from which I conclude that good ones are scarce among them.’ Captain James Cook. HMB Endeavour. 1769-70 in New Zealand. The hei tiki above was given to Captain James Cook by Māori at Queen Charlotte Sound in 1769 during his first voyage to the Pacific and New Zealand. It is now part of the Royal Collection and was probably given by Cook to George III (1738 - 1820) in 1771 upon his return to England. The King had personally sponsored Cook’s expedition. Cook’s journal entry concerning adzes of ‘green talc’ is not out of place in a discussion regarding tiki. It is evident that tiki were often fashioned from old pounamu toki blades, further adding to the mana of a piece that will have spent previous lifetimes in the hands of illustrious ancestors. A blade might be sharpened, shaped and further smoothed often in its working life but there will come a day when a new adze is required. Viewing a toki, one can easily imagine the blank of a hei tiki fitting nicely within its form. The proportions of a tiki quite neatly match the dimensions of the working face of a greenstone adze.

There was once a papakainga, or village, at Whareakeake, a small bay on the north side of Otago Peninsula 25km north east of Dunedin. If you’re ever down that way just look for Murdering Beach Road and follow it all the way to the sea. Surfers know how to get there. The bay features an excellent right-hand point break, especially when a Northeast swell conspires with a brisk Southerly breeze. Rad barrels Bro! But you can see how a village might have set itself easily in the landscape beside the winding stream, gentle in the lee of bluff and hillside. Archeological evidence strongly suggests that this village specialised in working pounamu. In December 1817, after prolonged tension and escalating violence between sealers and local Māori, matters came to a head with the arrival in the vicinity of the brig Sophia out of Hobart, Tasmania. Under the command of her master, Mr James Kelly, the Sophia left Tasmania on November 18th, 1817 and arrived back in Hobart 19 weeks later on the 22nd of March 1818 with 3000 seal skins and a tale of grim and bloody misadventure. Arriving in ‘Port Daniel’ (an early name for Port Otago, here referring to an anchorage in a bay near the substantial Māori settlement of Otakou) on or around the 11th of December 1817, there numbered among the crew a man named W. Tucker, called ‘Wioree’ by the local Māori. Tucker had lived at Whareakeake and had in fact built a house there some years before (around 1810 it is thought). He’d involved himself in the greenstone trade, selling souvenir pieces of New Zealand jade in Sydney. It has also been alleged that it was Tucker who took the tattooed head of a chief from the Riverton area to Sydney in 1810 or 1811, also for sale, thus beginning the business of trade in Mokomokai. Quite the entrepreneur, Mr Tucker, even without the head, though his business activities quite probably cost him his own. Upon arrival at Otakou the welcome is said to have been cordial enough. The following day saw Captain Kelly, Tucker and five other crewmen take the ship’s boat around to Whareakeake, ostensibly to trade for potatoes. Kelly is said to have made ‘…a small present of iron…’ for the chief there. At Whareakeake Kelly and his party were met by a ‘Lascar’, that is, a seaman of Asian descent, who told the men of the Sophia he had been left behind some years before (around 1813) by the brig Matilda out of Sydney bound for Tahiti. We are not given the Lascar’s name but it seems he’d fared well among the Māori of Whareakeake, unlike a gang of sealers who’d come to a sticky ending some years earlier, this news being imparted to Captain Kelly by the Lascar. Nonetheless, it seems that Captain Kelly and his men felt confident enough to seek an exchange with the Whareakeake locals. That would very soon turn out to be a fatal misjudgement. No sooner had Kelly’s party reached the chief’s house that ‘…in an instant an horrid yell was raised by the natives…’ And the men from the brig Sophia were immediately set upon. Remarkably, Kelly and four other men, including Tucker, made it back to the boat, presumably fighting all the way. The melee continued as the men struggled to gain the boat and put to sea and safety. Kelly and three other men named as Dutton, Wallon and Robinson made it. The unfortunate Tucker did not. He was knocked down in the breakers and was heard to cry ‘Captain Kelly, for God’s sake, don’t leave me.’ before being ‘cut limb from limb and being carried away by the savages.’ Two others of Kelly’s crew, Griffiths and Viole, were also terribly taken down and never seen again. Such are the ways of history.

This image is my toki. It represents the blade of an adze. It measures approximately 2.5 cm wide at the sharp end tapering to about 2 cm at the shoulder along a length of 5 cm. Someone dear to me gave it as a Christmas present in 2019. She asked Hohepa Bowen, whom we met in chapter two, to make one especially for me

From the grain of sand at the beach that might have been a mountain once, to the pendant at your neck that was birthed a hundred million years ago down deep where the rock is liquid and boiling, we humans know we are young in the universe. Our glory is that we know. We know because as a species we are predisposed to story. We evolved an inquisitive capacity that drives us still, to try and figure out the nature of things.