The House of Weaving: Part 1, The Most Important Dominions

According to many traditions, after Tāne Mahuta had separated his parents Ranginui [Sky father] and Papatuānuku [Earth mother], he placed te whānau marama, the family of light in the sky, including the sun, moon stars and other celestial bodies, to brighten his newly created world and try to bring comfort to his mother - and himself.

But Tāne couldn’t help feeling something was missing from his creation, something essential but somehow unknown to him. So he continued his search for. . . well, he didn’t really know - except that he was pretty sure he’d know it, when he found it.

While he was searching his newly created star laden heavens he came across Hinerauāmoa, the smallest, most fragile of the stars and yet, within this star he could feel a kind of strength and energy . . . and power that he had never felt, never known of before, and straight away he knew that this was what was missing from his world. Hinerauāmoa was te uha, the female element. From Tāne’s union with her came Hineteiwaiwa.

Te Whare Pora, the House of Weaving is the House of Hineteiwaiwa. She is the atua of the female arts, childbirth and the transmission of knowledge. In some traditions she is also Hina, the female personification of the moon and so, is in charge of the cycles of the moon. Of the female arts, weaving is of the greatest importance. Not only are the objects created beautiful, but in many ways, they guarantee the survival of the people.

When Tāwhirimatea rages at his brothers for separating his parents, bringing his winds and storms to bear; the work of the weavers keeps the wind and rain at bay with their rain capes and cloaks. When the Kumara needs to be carried, the kete are to hand. When the muka needs to be prepared from the harakeke, the weavers know the secrets of releasing the threads from the great leaves of flax.

From muka, the finest cloaks can be made. A net can be fashioned to feed the people, or even capture and hold the sun to convince him to slow his travel across the sky.

All manner of bindings can be twisted and plaited and braided together from muka. The delicate chord that hangs the tiki. The thong that keeps the blood soaked mere in hand after striking.

The lashings, chords and ropes that bind the ama to the waka, the kōmaru to the mast, the roof to the Whare and all the posts in the palisade are first and foremost threads of muka. Maui had a fishing line made of muka. Women from Te Whare Pora will have provided it.

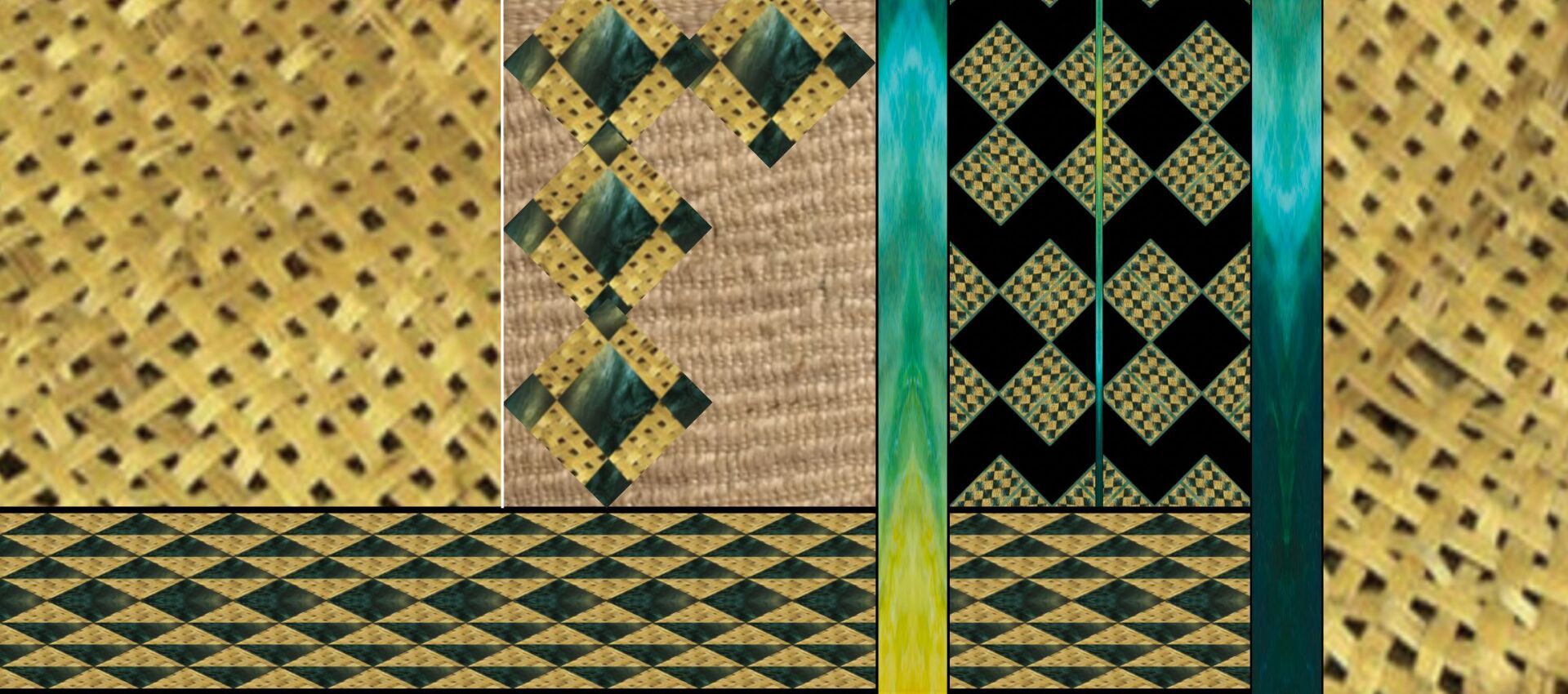

The tikanga of weaving is complex. Weavers need a thorough knowledge not only of the various techniques, but also the most appropriate materials; the fibres, threads, sinews, vines and so forth. How are these materials to be prepared?

When should they be gathered? And then the body of traditions that go with those materials. The harakeke alone, probably the plant most associated with weaving in Aotearoa, has enormous tikanga attached to it that goes far beyond the practical utility it provides through the garments, threads, chords, kete, matting and many things besides.

The plant that many people refer to as native or New Zealand flax is actually not a true flax at all. The fibres within the leaves give harakeke the flax reputation, though some would argue harakeke is the superior material.

True flax of course is the source of linen. Harakeke you could say, is the source of much more than that. For one thing, it is unlikely Māori would have survived here beyond a generation or two, without harakeke.

The stories and traditions associated with this plant of matchless mana in many respects reach into the very lives of the people, providing example and metaphor revealing family and tribal arrangement and the nature and strength through unity and cooperation.

The underlying story of harakeke is suggested in the name of the juvenile plant; the seedling, which is called Te Awhi Rito. Rito is the new shoot. Te Awhi - the supporting embrace.

If you observe the seedling, you will note the new young shoot in the centre. Fanning out on either side are three or four bigger leaves. Those leaves directly either side of Te Rito - think of it for a moment as a child - those first two leaves are called Mātua - Parents. The leaves either side of those are Kaumātua - Grandparents. All the leaves outside the Kaumātua; they are the Tūpuna leaves - the Ancestors.

You may notice that harakeke repeat this growing habit as the plant matures, surrounding itself with whānau as it goes. So the outermost leaves on a mature harakeke will always be Tūpuna leaves.

When you harvest harakeke for use, always harvest tūpuna leaves and never harvest Rito. Ever. And perhaps, if you’re wondering how to arrange yourselves in a new and somehow different land than the islands and faraway places you came here from, you might consider observing a harakeke for a while.

And still there are techniques, correct procedures and other plants to learn about across all the weaving disciplines; Whatu, Whiri, Taniko and Tukutuku, Raranga and Whāriki.

Patience, perseverance, strong focus and concentration for long periods, methodical, dextrous, delicate yet strong, possessed of great stamina, a capacity to memorise and recall an immense body of tikanga and kōrero and to recall it accurately and completely; these are many, but not all of the attributes of the women of Te Whare Pora.

Perhaps this is why the Matriarch of the Whare has been assigned the most important dominions. Hineteiwaiwa will bear the child; weave the cloth that keeps it wrapped, secure and warm, and compose and sing the oriori - the lullabies that begin the communication of whakapapa, knowledge and wisdom.

In

Te Whare Pora, Part 2: Tuatahi, Te Muka - First, the Muka we’ll explore the muka, the secret strength of harakeke; how its released from the tūpuna and the techniques used to turn it into works of beauty and utility. We’ll also see how different needs led to other styles and techniques being developed to accomodate more functional kete, matting, panelling and belting uses as well as binding, chords and lashing.