FREE SHIPPING WITHIN NEW ZEALAND AND ORDERS OVER $50 TO AUSTRALIA

Design Elements of the Maori Carving Arts

NGĀ AHUATANGA HOAHOA

O TE TOI WHAKAIRO

MĀORI

DESIGN ELEMENTS OF

THE MĀORI CARVING

ARTS

A BLOG FOR MOKO POUNAMU.

Ben Brown. October 2022.

PART 3

ADORNING

THE NARRATIVE

All Māori art has narrative. Every part of the wharenui, every element contributes to the story of the House. Within each major piece, each pou, each tukutuku panel, each kōwhaiwhai decorated rafter, there are narratives, stories, reminders and cues, references to spiritual and earthly requirements, lessons that remain constant. Narratives can be structured any number of ways depending on the nature and purpose of the story. Placement and unity or discord of symbols. Proximity and scale. How void spaces engage with solid and with light. How relief yields depth and suggests movement. These are all considerations the tohunga whakairo, the carving expert must weigh, assess and eventually render according to their own judgements, aesthetic sense and abilities.

Modern tools and materials, contemporary themes and new applications, all offer the carvers of today so many varied and wonderful opportunities to extend and progress their artform, in a sense, creating new tikanga - the right and proper practices and procedures - as they go. Still the one imperative will remain. Whatever the object, once whakairo technique is applied, so too has a narrative commenced. The decorative embellishment on the handle of a heru - a hair comb - whether rendered as a spiral in relief as a relatively simple motif, or more elaborately decorated with the use of void spaces to render koru, pītau (takarangi) or pikorua for instance, these examples all have in them the beginnings of a narrative according to the meanings and symbolism of the chosen design. But also in the person for whom the comb is intended, their story, or some specific element contained therein might be imagined as having some consequence or emphasis accentuated by the presence, use or even just the possession of a heru with a handle design that speaks appropriately to the head whose hair it will groom and keep in place.

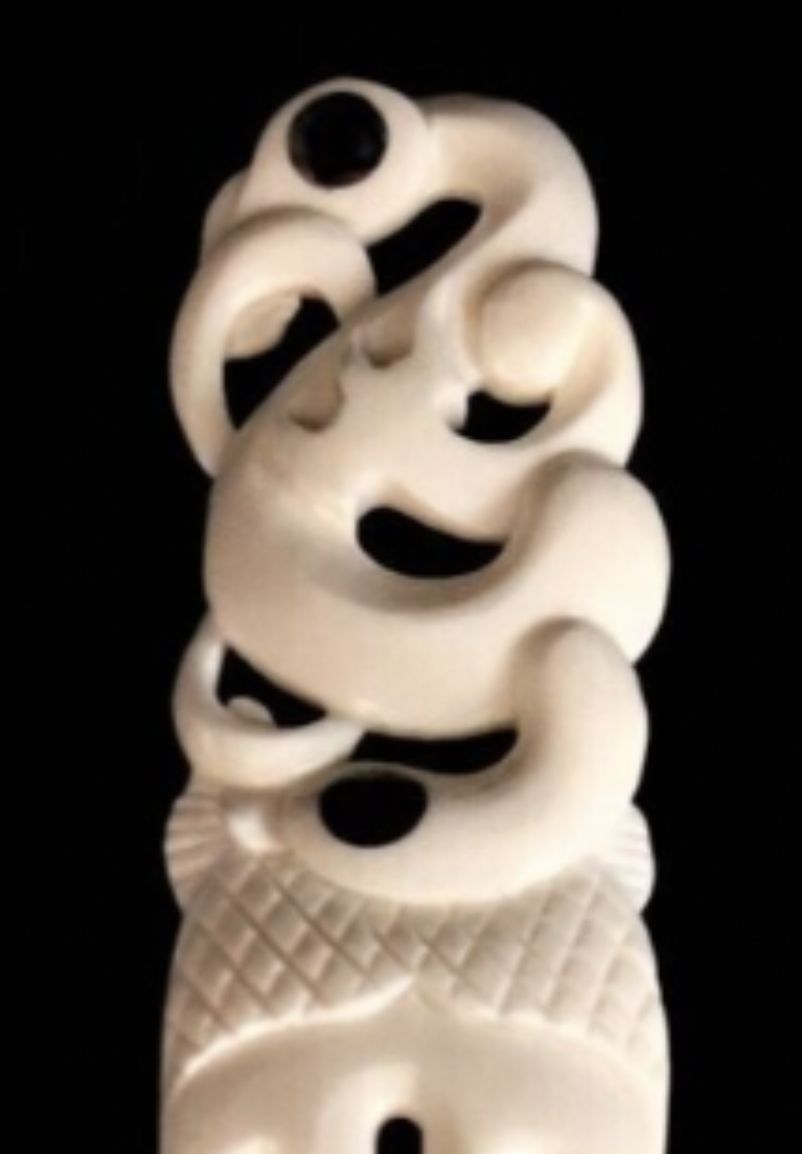

This manaia heru offers a spiritual narrative with the association of the manaia to that of a messenger between the earthly and spiritual dimensions but more importantly I think, by its physical presence, its real attendance on this heru as an adornment for someone’s head - the most tapu or spiritually important part of the human body as far as tikanga is concerned; to me, it talks to the idea that in a Māori world view, the Spiritual aspect or dimension is not remote but carried along with us in the living of our lives and even within us, and that we, to a certain extent are carried along either within or beside or as part of an all encompassing Physical Spiritual universe, in which case I imagine anyone drawn to spiritual enquiry might find some extra association or interest in such an object beyond that of a decorative adornment. Void spaces alternating with solid have similar allusions to the eternal interconnectedness of the living to the past, of the world of light, te ao marama - to te pō and the eternal night of those who have passed on and left us here to get on with things and indeed, to the collective mana

accumulated as the legacy and responsibility handed down to us as whakapapa. While the gentle suggestions of koru incorporated into the body and forming aspects of the manaia speaking to growth and renewal is not out of place at all in the narrative so far revealed, only adding to the idea that we, the living are aware of our deeper responsibilities. There is also present what appears to me as a pattern style much in the vein of niho taniwha - taniwha teeth - where the manaia figure sits and the patterning drapes the top of the comb piece almost as a whāriki woven mat, in the shape of a fishtail.

Taniwha are supernatural beings sometimes described as a ‘dragon’ or ‘monster’, sometimes as a great fish or some other extraordinary creature. Taniwha are powerful, often magical and often as well they are dutiful in the role of guardian and protecter to

a particular place and people. Generally they are said to live or dwell either in the waters or the earth. Some of them are shape changers and may even take human form. I am from the Waikato tribes Ngāti Mahuta and Ngāti Koroki and we hold the Taniwha sacred as a symbol and example of tribal identity; Waikato taniwharau he piko he taniwha he piko he taniwha - Waikato of a hundred Taniwha, on every bend, a taniwha. Metaphorically, this pepeha alludes to the many great chiefs who came from the Waikato river tribes. There are places along the Waikato river where, for many miles, there was literally a Pā, and therefor a chief on every bend. If it is niho taniwha, the associations are of a chiefly lineage all the way to the gods. It can also pertain to the whanau houses set within a Pā or papa kainga among the people. The teeth have been said to represent the ‘historian’ as well. Not just as we might think of the gatherer of such stories. But also as an explorer of origin, wherein gods, demi gods and a host of other beings and personifications existed for a time alongside human men, women and children from every conceivable frame of reference, Here then, within the heru, we can perhaps begin to understand and appreciate the narrative range and depth that might be attained by the tohunga whakairo.

Ben Brown October 2022.

Become a Moko Club Member

Thanks for becoming a Moko Club Member

Oops, there was a slight error when you hit Join.

Please try again after a few minutes.